Marcel Duchamp Giclée Fine Art Prints

1887-1968

French Dadaist/Surrealist Artist

Marcel Duchamp's trajectory through twentieth-century art reads less as a conventional artist's biography than as an intellectual odyssey that fundamentally altered our understanding of what art might be. Born in Blainville on July 28, 1887, into a bourgeois family headed by a notary, Duchamp emerged from an unexpectedly artistic lineage - his grandfather, though a shipping agent by profession, pursued engraving with serious dedication. This familial predisposition manifested itself remarkably: four of the six Duchamp children would become artists, with his elder brothers Gaston and Raymond adopting the professional names Jacques Villon and Duchamp-Villon respectively.

When the young Marcel arrived in Paris in October 1904, he found himself advantageously positioned through his brothers' established connections. Yet from the outset, his approach diverged from expected patterns. His early Portrait of Marcel Lefrançois demonstrated technical competence and stylistic assurance, but Duchamp would never be content with mastery alone. During these formative years, while supporting himself through cartoon illustrations for comic magazines, he moved through contemporary movements - Post-Impressionism, Cézanne's influence, Fauvism, Cubism - with the detachment of a scientist conducting experiments rather than an artist seeking his voice.

This experimental stance produced curious temporal dislocations in his work. His Portrait of the Artist's Father, executed in Fauvist style, appeared three or four years after the movement had effectively concluded. Such chronological independence suggests not dilettantism but rather a fundamental skepticism about artistic movements themselves. By 1911, when traces of Cubism began to surface in his work, Duchamp had formed crucial friendships with Guillaume Apollinaire and Francis Picabia. With Picabia especially, he shared a restlessness about Cubism's systematic nature, finding it "boring" - a damning assessment that would propel both artists toward more radical territories.

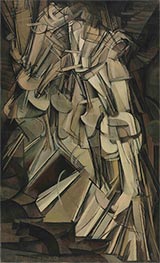

The path to Duchamp's most notorious early work began with Portrait (Dulcinea) in 1911, its five superimposed, near-monochromatic silhouettes introducing the serial depiction of movement. This exploration culminated in Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), where the figure dissolves entirely into what Duchamp himself characterized as "a descending machine." The painting's rejection by the committee of the 1912 Salon des Indépendants - a group including family friends hardly hostile to modernism - and its subsequent scandalous success at New York's Armory Show in 1913, precipitated Duchamp's most radical decision: to abandon painting at twenty-five.

The works immediately following the Nude - particularly Le Passage de la Vierge à la Mariée and Mariée, both created in Munich - demonstrate that Duchamp's withdrawal from painting stemmed not from any technical limitation but from philosophical conviction. These paintings, neither strictly Cubist nor Futurist nor Abstract, articulated his singular vision of corporeality perceived through its deepest impulses. Yet they would be among his last conventional paintings.

Duchamp's disillusionment with what he dismissively termed "retinal art" led him toward The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, known as The Large Glass. Begun in 1913 and abandoned as "definitively unfinished" in 1923, this work adopted industrial design's geometrical methods to create a symbolic blueprint exploring themes of desire and mechanical reproduction. Parallel to this decade-long project, Duchamp's 1913 Bicycle Wheel initiated the revolutionary concept of the ready-made - ordinary objects designated as art through selection rather than creation.

His 1915 arrival in New York, precipitated by World War I, marked a crucial transition. Welcomed as a celebrity following the Nude's notoriety, Duchamp nonetheless resisted commercial opportunities, supporting himself through French lessons rather than capitalizing on his reputation. The hospitality of Walter Arensberg provided both studio space and intellectual community, yet Duchamp maintained his distance from professional artistic identity. His ready-mades of this period - including the infamous urinal titled Fountain, submitted under the pseudonym "R. Mutt" to the 1917 Society of Independent Artists exhibition - anticipated and influenced the emerging Dada movement.

The interwar period saw Duchamp's interests shift toward kinetic and optical experiments, culminating in the film Anemic Cinema (1926). His absorption in chess - he competed internationally and published a treatise in 1932 - appeared to signal complete withdrawal from art production. Yet his involvement with Surrealism, particularly his collaboration with André Breton in organizing exhibitions from 1938 to 1959, maintained his presence in artistic discourse while preserving his outsider status.

Duchamp's wartime return to New York, smuggling components of his Boîte-en-valise across occupied France, initiated his final American period. His 1954 marriage to Teeny Sattler coincided with increasing semiretirement, though the 1960s brought unexpected recognition from a new generation discovering in his work solutions to their own artistic problems. The posthumous revelation of Étant donnés, secretly created over twenty years, demonstrated that even Duchamp's silence had been a form of artistic statement.

To comprehend Duchamp's significance requires abandoning conventional metrics of artistic achievement. His production was deliberately minimal, his engagement with the art market virtually nonexistent, his public persona carefully cultivated to suggest indifference. Yet through gestures of negation - the ready-made's challenge to craftsmanship, The Large Glass's rejection of visual pleasure, his abandonment of painting itself - Duchamp redefined artistic possibility. His legacy resides not in a body of work but in a fundamental reorientation of art's relationship to intellect, to ordinary objects, and to its own traditions. In transforming the artist from maker to chooser, from craftsman to philosopher, Duchamp created space for virtually every subsequent challenge to artistic orthodoxy. His true medium was not paint or found objects but the idea of art itself.

When the young Marcel arrived in Paris in October 1904, he found himself advantageously positioned through his brothers' established connections. Yet from the outset, his approach diverged from expected patterns. His early Portrait of Marcel Lefrançois demonstrated technical competence and stylistic assurance, but Duchamp would never be content with mastery alone. During these formative years, while supporting himself through cartoon illustrations for comic magazines, he moved through contemporary movements - Post-Impressionism, Cézanne's influence, Fauvism, Cubism - with the detachment of a scientist conducting experiments rather than an artist seeking his voice.

This experimental stance produced curious temporal dislocations in his work. His Portrait of the Artist's Father, executed in Fauvist style, appeared three or four years after the movement had effectively concluded. Such chronological independence suggests not dilettantism but rather a fundamental skepticism about artistic movements themselves. By 1911, when traces of Cubism began to surface in his work, Duchamp had formed crucial friendships with Guillaume Apollinaire and Francis Picabia. With Picabia especially, he shared a restlessness about Cubism's systematic nature, finding it "boring" - a damning assessment that would propel both artists toward more radical territories.

The path to Duchamp's most notorious early work began with Portrait (Dulcinea) in 1911, its five superimposed, near-monochromatic silhouettes introducing the serial depiction of movement. This exploration culminated in Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), where the figure dissolves entirely into what Duchamp himself characterized as "a descending machine." The painting's rejection by the committee of the 1912 Salon des Indépendants - a group including family friends hardly hostile to modernism - and its subsequent scandalous success at New York's Armory Show in 1913, precipitated Duchamp's most radical decision: to abandon painting at twenty-five.

The works immediately following the Nude - particularly Le Passage de la Vierge à la Mariée and Mariée, both created in Munich - demonstrate that Duchamp's withdrawal from painting stemmed not from any technical limitation but from philosophical conviction. These paintings, neither strictly Cubist nor Futurist nor Abstract, articulated his singular vision of corporeality perceived through its deepest impulses. Yet they would be among his last conventional paintings.

Duchamp's disillusionment with what he dismissively termed "retinal art" led him toward The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, known as The Large Glass. Begun in 1913 and abandoned as "definitively unfinished" in 1923, this work adopted industrial design's geometrical methods to create a symbolic blueprint exploring themes of desire and mechanical reproduction. Parallel to this decade-long project, Duchamp's 1913 Bicycle Wheel initiated the revolutionary concept of the ready-made - ordinary objects designated as art through selection rather than creation.

His 1915 arrival in New York, precipitated by World War I, marked a crucial transition. Welcomed as a celebrity following the Nude's notoriety, Duchamp nonetheless resisted commercial opportunities, supporting himself through French lessons rather than capitalizing on his reputation. The hospitality of Walter Arensberg provided both studio space and intellectual community, yet Duchamp maintained his distance from professional artistic identity. His ready-mades of this period - including the infamous urinal titled Fountain, submitted under the pseudonym "R. Mutt" to the 1917 Society of Independent Artists exhibition - anticipated and influenced the emerging Dada movement.

The interwar period saw Duchamp's interests shift toward kinetic and optical experiments, culminating in the film Anemic Cinema (1926). His absorption in chess - he competed internationally and published a treatise in 1932 - appeared to signal complete withdrawal from art production. Yet his involvement with Surrealism, particularly his collaboration with André Breton in organizing exhibitions from 1938 to 1959, maintained his presence in artistic discourse while preserving his outsider status.

Duchamp's wartime return to New York, smuggling components of his Boîte-en-valise across occupied France, initiated his final American period. His 1954 marriage to Teeny Sattler coincided with increasing semiretirement, though the 1960s brought unexpected recognition from a new generation discovering in his work solutions to their own artistic problems. The posthumous revelation of Étant donnés, secretly created over twenty years, demonstrated that even Duchamp's silence had been a form of artistic statement.

To comprehend Duchamp's significance requires abandoning conventional metrics of artistic achievement. His production was deliberately minimal, his engagement with the art market virtually nonexistent, his public persona carefully cultivated to suggest indifference. Yet through gestures of negation - the ready-made's challenge to craftsmanship, The Large Glass's rejection of visual pleasure, his abandonment of painting itself - Duchamp redefined artistic possibility. His legacy resides not in a body of work but in a fundamental reorientation of art's relationship to intellect, to ordinary objects, and to its own traditions. In transforming the artist from maker to chooser, from craftsman to philosopher, Duchamp created space for virtually every subsequent challenge to artistic orthodoxy. His true medium was not paint or found objects but the idea of art itself.

6 Marcel Duchamp Artworks

Giclée Canvas Print

$61.41

$61.41

SKU: 17712-DUC

Marcel Duchamp

Original Size:147 x 89.2 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA

Marcel Duchamp

Original Size:147 x 89.2 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$72.60

$72.60

SKU: 19921-DUC

Marcel Duchamp

Original Size:145 x 113.3 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA

Marcel Duchamp

Original Size:145 x 113.3 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$61.41

$61.41

SKU: 19924-DUC

Marcel Duchamp

Original Size:89.5 x 55.6 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA

Marcel Duchamp

Original Size:89.5 x 55.6 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$92.23

$92.23

SKU: 19922-DUC

Marcel Duchamp

Original Size:100.6 x 100.5 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA

Marcel Duchamp

Original Size:100.6 x 100.5 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$83.09

$83.09

SKU: 19923-DUC

Marcel Duchamp

Original Size:114.6 x 129 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA

Marcel Duchamp

Original Size:114.6 x 129 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$72.10

$72.10

SKU: 19920-DUC

Marcel Duchamp

Original Size:146.4 x 114 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA

Marcel Duchamp

Original Size:146.4 x 114 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA