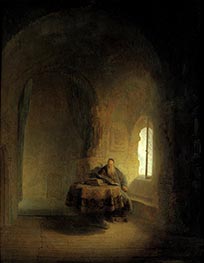

van Rijn Rembrandt Giclée Fine Art Prints 1 of 12

1606-1669

Dutch Baroque Painter

The trajectory of Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn's life presents a compelling study in artistic evolution and social mobility. Born on July 15, 1606, in Leiden, he emerged from circumstances that were neither privileged nor particularly conducive to artistic greatness. His father, Harmen Gerritszoon van Rijn, operated a mill, while his mother, Neeltgen Willemsdochter van Zuytbrouck, came from a family of bakers - occupations that placed the family firmly within the working middle class of Dutch society.

The fourth of six surviving children from ten births, Rembrandt's early years were marked by an education that, while not exceptional, provided crucial foundations. His attendance at elementary school from approximately 1612 to 1616, followed by enrollment at the Latin School in Leiden until 1620, exposed him to biblical studies and classical texts. The emphasis on oratory skills at the Latin School would prove particularly significant, arguably contributing to his later facility in staging figures within complex narrative compositions. His brief registration at Leiden University in May 1620 appears to have been more a formality than a serious academic pursuit - a common practice among Latin School graduates seeking tax advantages rather than scholarly advancement.

The period from 1620 to 1625 marks Rembrandt's formal artistic training, undertaken with a methodical approach typical of the era. His first master, Jacob van Swanenburgh, a Leiden painter specializing in architectural pieces and infernal scenes, provided fundamental technical instruction over approximately three years. Van Swanenburgh's particular expertise in rendering fire and its reflections on surrounding surfaces introduced the young artist to complex problems of light - a preoccupation that would become central to Rembrandt's mature work. The subsequent six months spent with Pieter Lastman in Amsterdam proved transformative. Lastman, established as a history painter of considerable reputation, imparted the sophisticated skills required for managing multiple figures within elaborate settings, handling the full range of subjects from landscape to human form that this most prestigious genre demanded.

Rembrandt's return to Leiden around 1625 as an independent master initiated a period of intense productivity and experimentation. His earliest works from this period reveal a systematic deconstruction and reconstruction of Lastman's compositional methods - a process of artistic digestion that went beyond mere imitation. The small-scale history paintings and tronies that dominated his output during these years demonstrate a young artist grappling with fundamental questions of light, texture, and narrative expression. His probable collaboration with Jan Lievens, one year his junior but already an accomplished artist, created a competitive dynamic that accelerated both painters' development.

The revolutionary transformation in Rembrandt's approach between 1627 and 1629 centered on his radical reconsideration of light's function within pictorial space. Moving beyond the even illumination characteristic of his earliest works, he developed what might be termed a spotlight methodology - concentrating light sources to create dramatic contrasts while necessarily consigning large areas to shadow. This approach, reminiscent of Caravaggio's innovations, required compensatory adjustments in color and detail to maintain compositional unity. His system of "bevriende kleuren" or kindred colors, clustering related hues within illuminated areas while surrounding them with coherent darker tones, achieved both intensity and cohesion.

The decision to begin etching around 1628 represented a calculated expansion of artistic practice rather than a casual experiment. Unlike drawing, which naturally complements painting, etching demanded mastery of an entirely different technical vocabulary. Rembrandt's approach to the medium was characteristically unconventional - eschewing the regular, controlled line work typical of contemporary engravers in favor of a freer, more painterly technique that initially appeared almost nervous in its execution. This apparent lack of control was, in fact, a sophisticated strategy for achieving atmospheric effects and suggesting the play of light through varied methods of hatching.

His role as a teacher, beginning with Gerrit Dou in 1628 and continuing until approximately 1663, reveals another dimension of Rembrandt's professional practice. The substantial fee of 100 guilders annually - paid without the customary provision of board - indicates the premium placed on his instruction. The stream of pupils, estimated conservatively at fifty over his career but possibly many more, included significant talents such as Govaert Flinck, Carel Fabritius, and Aert de Gelder. The workshop structure, with pupils occupying individual cubicles partitioned by sailcloth or paper in the attic, facilitated both concentrated study and the production of marketable works in the master's manner.

The relocation to Amsterdam in 1631 and association with Hendrick Uylenburgh's workshop marked a strategic pivot in Rembrandt's career. The four years spent in Uylenburgh's establishment, likely serving as head of workshop while navigating guild regulations that required a probationary period before independent practice, saw him conquer the lucrative portrait market. His portraits from this period demonstrate a synthesis of his history painting experience with portraiture's specific demands - achieving liveliness through simplified detail and dynamic contours while maintaining convincing representation of flesh and fabric. The question of whether these portraits achieved accurate likenesses remains contentious, with contemporary evidence suggesting that formal resemblance may have been subordinated to artistic effect.

The production of biblical subjects during the Uylenburgh years raises intriguing questions about Rembrandt's religious affiliations. Born to a Reformed father and Catholic mother, he appears to have maintained a deliberate distance from sectarian identification. His children's infant baptisms preclude Anabaptist membership, while his manner of living contradicted that community's austere expectations. The sympathetic treatment of Jewish subjects and Old Testament narratives, coupled with his documented association with Rabbi Manasseh ben Israel, suggests a broadly humanistic approach to religious difference that transcended contemporary denominational boundaries.

The year 1635 marked Rembrandt's establishment as an independent householder, culminating in the 1639 purchase of a substantial property built in 1606-07. The financing arrangement - with less than one-third paid initially - would prove fateful. The two decades spent in this house witnessed both the zenith of his public success and the emergence of financial difficulties that would eventually force its sale. The acquisitive impulse that led to the assembly of an extensive kunstkamer - documented in devastating detail in the 1656 bankruptcy inventory - reveals a collector whose passion for objects both natural and artificial may have exceeded prudent limits.

The execution of the militia company portrait later known as the Night Watch between 1640 and 1642 represents both a culmination and a crisis point. Rembrandt's radical reconception of group portraiture - subordinating individual likenesses to overall compositional unity - pushed his evolved pictorial language to its limits. The double spotlight effect created by the illuminated figures of the girl and lieutenant, both in yellow costumes, created tonal complications that darkened the overall impression. Samuel van Hoogstraten's criticism regarding insufficient light, despite his praise for the work's unity, points to the technical impasse Rembrandt had reached.

The decade following 1642 witnessed a dramatic reduction in painted output and an apparent withdrawal from the portrait market. Whether this resulted from lack of commissions or deliberate choice remains unclear. The period's sparse production shows remarkable stylistic variation, suggesting an artist seeking new solutions to self-imposed pictorial problems. The introduction of multiple light sources, the return of strong color (particularly red) to central compositional positions, and experiments with frontal rather than diagonal arrangements all indicate systematic reconsideration of established methods.

The emergence of what is conventionally termed Rembrandt's late style around 1650 involved a fundamental shift toward a manner inspired by late Titian. The broader, more visible brushwork, the apparently accidental quality of paint application, and the strategic use of impasto to create light-reflecting surfaces in foreground passages all contributed to a style that required viewing from a specific distance for full effect. This freedom of execution, paradoxically combined with intensified observation, created works of remarkable psychological penetration despite - or perhaps because of - the reduction in explicit gesture and movement.

The financial crisis culminating in the 1656 bankruptcy must be understood within broader economic contexts. The first Anglo-Dutch War's disruption of luxury goods markets affected numerous artists and craftsmen. Rembrandt's failure to discharge the debt on his house, combined with the cessation of portrait commissions after 1642 and continued collecting, created an untenable situation. The arrangement established in 1660, whereby he effectively worked for his son Titus and Hendrickje Stoffels, protected him from creditors while enabling continued production.

Evidence of Rembrandt's sustained reputation emerges from various sources. Prince Cosimo de' Medici's visits in 1667 and 1669, during which Rembrandt was designated "pittore famoso," and Gabriel Bucelinus's annotation of him as "nostrae aetatis miraculum" among 166 distinguished European painters, confirm continued esteem. Yet his absence from prestigious commissions such as the Oranjezaal decorations and his secondary involvement in the Amsterdam Town Hall project reveal an artist whose uncompromising approach may have limited official recognition.

The characterization of Rembrandt as an "umorista of the first order" who "disdained everybody," refusing to interrupt work even for monarchs, suggests an personality prioritizing artistic integrity over social accommodation. This uncompromising nature, combined with the reported negligence of dress and manner, created a figure whose devotion to work superseded conventional proprieties. The late portraits, including the Sampling Officials of 1662 and the so-called Jewish Bride of 1667, demonstrate sustained technical mastery despite reduced circumstances.

Rembrandt's death on October 4, 1669, and burial in the Westerkerk concluded a career of extraordinary productivity and innovation. The myth of the impoverished, misunderstood genius, while containing elements of truth regarding his financial difficulties and the shift in taste toward Classicism, obscures the reality of an artist who maintained significant reputation and continued working at the highest level until the end. His legacy - in the revolutionary treatment of light, the psychological penetration of his portraits, the technical innovations across multiple media, and the model of artistic development that never ceased evolving - established parameters that would influence subsequent centuries of artistic practice. The corpus of work left behind, complicated by attribution questions arising from workshop practices, remains a testament to an artistic intelligence that combined acute observation with unparalleled technical facility in the service of human understanding.

The fourth of six surviving children from ten births, Rembrandt's early years were marked by an education that, while not exceptional, provided crucial foundations. His attendance at elementary school from approximately 1612 to 1616, followed by enrollment at the Latin School in Leiden until 1620, exposed him to biblical studies and classical texts. The emphasis on oratory skills at the Latin School would prove particularly significant, arguably contributing to his later facility in staging figures within complex narrative compositions. His brief registration at Leiden University in May 1620 appears to have been more a formality than a serious academic pursuit - a common practice among Latin School graduates seeking tax advantages rather than scholarly advancement.

The period from 1620 to 1625 marks Rembrandt's formal artistic training, undertaken with a methodical approach typical of the era. His first master, Jacob van Swanenburgh, a Leiden painter specializing in architectural pieces and infernal scenes, provided fundamental technical instruction over approximately three years. Van Swanenburgh's particular expertise in rendering fire and its reflections on surrounding surfaces introduced the young artist to complex problems of light - a preoccupation that would become central to Rembrandt's mature work. The subsequent six months spent with Pieter Lastman in Amsterdam proved transformative. Lastman, established as a history painter of considerable reputation, imparted the sophisticated skills required for managing multiple figures within elaborate settings, handling the full range of subjects from landscape to human form that this most prestigious genre demanded.

Rembrandt's return to Leiden around 1625 as an independent master initiated a period of intense productivity and experimentation. His earliest works from this period reveal a systematic deconstruction and reconstruction of Lastman's compositional methods - a process of artistic digestion that went beyond mere imitation. The small-scale history paintings and tronies that dominated his output during these years demonstrate a young artist grappling with fundamental questions of light, texture, and narrative expression. His probable collaboration with Jan Lievens, one year his junior but already an accomplished artist, created a competitive dynamic that accelerated both painters' development.

The revolutionary transformation in Rembrandt's approach between 1627 and 1629 centered on his radical reconsideration of light's function within pictorial space. Moving beyond the even illumination characteristic of his earliest works, he developed what might be termed a spotlight methodology - concentrating light sources to create dramatic contrasts while necessarily consigning large areas to shadow. This approach, reminiscent of Caravaggio's innovations, required compensatory adjustments in color and detail to maintain compositional unity. His system of "bevriende kleuren" or kindred colors, clustering related hues within illuminated areas while surrounding them with coherent darker tones, achieved both intensity and cohesion.

The decision to begin etching around 1628 represented a calculated expansion of artistic practice rather than a casual experiment. Unlike drawing, which naturally complements painting, etching demanded mastery of an entirely different technical vocabulary. Rembrandt's approach to the medium was characteristically unconventional - eschewing the regular, controlled line work typical of contemporary engravers in favor of a freer, more painterly technique that initially appeared almost nervous in its execution. This apparent lack of control was, in fact, a sophisticated strategy for achieving atmospheric effects and suggesting the play of light through varied methods of hatching.

His role as a teacher, beginning with Gerrit Dou in 1628 and continuing until approximately 1663, reveals another dimension of Rembrandt's professional practice. The substantial fee of 100 guilders annually - paid without the customary provision of board - indicates the premium placed on his instruction. The stream of pupils, estimated conservatively at fifty over his career but possibly many more, included significant talents such as Govaert Flinck, Carel Fabritius, and Aert de Gelder. The workshop structure, with pupils occupying individual cubicles partitioned by sailcloth or paper in the attic, facilitated both concentrated study and the production of marketable works in the master's manner.

The relocation to Amsterdam in 1631 and association with Hendrick Uylenburgh's workshop marked a strategic pivot in Rembrandt's career. The four years spent in Uylenburgh's establishment, likely serving as head of workshop while navigating guild regulations that required a probationary period before independent practice, saw him conquer the lucrative portrait market. His portraits from this period demonstrate a synthesis of his history painting experience with portraiture's specific demands - achieving liveliness through simplified detail and dynamic contours while maintaining convincing representation of flesh and fabric. The question of whether these portraits achieved accurate likenesses remains contentious, with contemporary evidence suggesting that formal resemblance may have been subordinated to artistic effect.

The production of biblical subjects during the Uylenburgh years raises intriguing questions about Rembrandt's religious affiliations. Born to a Reformed father and Catholic mother, he appears to have maintained a deliberate distance from sectarian identification. His children's infant baptisms preclude Anabaptist membership, while his manner of living contradicted that community's austere expectations. The sympathetic treatment of Jewish subjects and Old Testament narratives, coupled with his documented association with Rabbi Manasseh ben Israel, suggests a broadly humanistic approach to religious difference that transcended contemporary denominational boundaries.

The year 1635 marked Rembrandt's establishment as an independent householder, culminating in the 1639 purchase of a substantial property built in 1606-07. The financing arrangement - with less than one-third paid initially - would prove fateful. The two decades spent in this house witnessed both the zenith of his public success and the emergence of financial difficulties that would eventually force its sale. The acquisitive impulse that led to the assembly of an extensive kunstkamer - documented in devastating detail in the 1656 bankruptcy inventory - reveals a collector whose passion for objects both natural and artificial may have exceeded prudent limits.

The execution of the militia company portrait later known as the Night Watch between 1640 and 1642 represents both a culmination and a crisis point. Rembrandt's radical reconception of group portraiture - subordinating individual likenesses to overall compositional unity - pushed his evolved pictorial language to its limits. The double spotlight effect created by the illuminated figures of the girl and lieutenant, both in yellow costumes, created tonal complications that darkened the overall impression. Samuel van Hoogstraten's criticism regarding insufficient light, despite his praise for the work's unity, points to the technical impasse Rembrandt had reached.

The decade following 1642 witnessed a dramatic reduction in painted output and an apparent withdrawal from the portrait market. Whether this resulted from lack of commissions or deliberate choice remains unclear. The period's sparse production shows remarkable stylistic variation, suggesting an artist seeking new solutions to self-imposed pictorial problems. The introduction of multiple light sources, the return of strong color (particularly red) to central compositional positions, and experiments with frontal rather than diagonal arrangements all indicate systematic reconsideration of established methods.

The emergence of what is conventionally termed Rembrandt's late style around 1650 involved a fundamental shift toward a manner inspired by late Titian. The broader, more visible brushwork, the apparently accidental quality of paint application, and the strategic use of impasto to create light-reflecting surfaces in foreground passages all contributed to a style that required viewing from a specific distance for full effect. This freedom of execution, paradoxically combined with intensified observation, created works of remarkable psychological penetration despite - or perhaps because of - the reduction in explicit gesture and movement.

The financial crisis culminating in the 1656 bankruptcy must be understood within broader economic contexts. The first Anglo-Dutch War's disruption of luxury goods markets affected numerous artists and craftsmen. Rembrandt's failure to discharge the debt on his house, combined with the cessation of portrait commissions after 1642 and continued collecting, created an untenable situation. The arrangement established in 1660, whereby he effectively worked for his son Titus and Hendrickje Stoffels, protected him from creditors while enabling continued production.

Evidence of Rembrandt's sustained reputation emerges from various sources. Prince Cosimo de' Medici's visits in 1667 and 1669, during which Rembrandt was designated "pittore famoso," and Gabriel Bucelinus's annotation of him as "nostrae aetatis miraculum" among 166 distinguished European painters, confirm continued esteem. Yet his absence from prestigious commissions such as the Oranjezaal decorations and his secondary involvement in the Amsterdam Town Hall project reveal an artist whose uncompromising approach may have limited official recognition.

The characterization of Rembrandt as an "umorista of the first order" who "disdained everybody," refusing to interrupt work even for monarchs, suggests an personality prioritizing artistic integrity over social accommodation. This uncompromising nature, combined with the reported negligence of dress and manner, created a figure whose devotion to work superseded conventional proprieties. The late portraits, including the Sampling Officials of 1662 and the so-called Jewish Bride of 1667, demonstrate sustained technical mastery despite reduced circumstances.

Rembrandt's death on October 4, 1669, and burial in the Westerkerk concluded a career of extraordinary productivity and innovation. The myth of the impoverished, misunderstood genius, while containing elements of truth regarding his financial difficulties and the shift in taste toward Classicism, obscures the reality of an artist who maintained significant reputation and continued working at the highest level until the end. His legacy - in the revolutionary treatment of light, the psychological penetration of his portraits, the technical innovations across multiple media, and the model of artistic development that never ceased evolving - established parameters that would influence subsequent centuries of artistic practice. The corpus of work left behind, complicated by attribution questions arising from workshop practices, remains a testament to an artistic intelligence that combined acute observation with unparalleled technical facility in the service of human understanding.

285 Rembrandt Artworks

Page 1 of 12

Giclée Canvas Print

$75.29

$75.29

SKU: 2002-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:161.7 x 129.8 cm

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, USA

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:161.7 x 129.8 cm

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$77.51

$77.51

SKU: 9102-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:72.8 x 60.3 cm

Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart, Germany

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:72.8 x 60.3 cm

Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$72.39

$72.39

SKU: 2027-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:262 x 205 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:262 x 205 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Giclée Canvas Print

$79.35

$79.35

SKU: 9014-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:55.1 x 46.5 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:55.1 x 46.5 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

Giclée Canvas Print

$61.81

$61.81

SKU: 10540-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:52.4 x 37 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:52.4 x 37 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$72.73

$72.73

SKU: 2015-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:83.8 x 65.4 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:83.8 x 65.4 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

Giclée Canvas Print

$74.95

$74.95

SKU: 8888-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:161 x 131 cm

Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:161 x 131 cm

Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$61.81

$61.81

SKU: 8922-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:15.6 x 12.7 cm

Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Germany

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:15.6 x 12.7 cm

Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$75.45

$75.45

SKU: 4261-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:75 x 93 cm

Liechtenstein Museum, Vienna, Austria

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:75 x 93 cm

Liechtenstein Museum, Vienna, Austria

Giclée Canvas Print

$119.62

$119.62

SKU: 9067-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:73 x 94 cm

Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, Russia

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:73 x 94 cm

Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, Russia

Giclée Canvas Print

$68.99

$68.99

SKU: 9097-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:44.5 x 60 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:44.5 x 60 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Giclée Canvas Print

$109.19

$109.19

SKU: 2005-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:185 x 203 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:185 x 203 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Giclée Canvas Print

$76.83

$76.83

SKU: 10534-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:135 x 111 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:135 x 111 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Giclée Canvas Print

$69.83

$69.83

SKU: 9087-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:67.5 x 50.7 cm

Kaiser-Friedrich-Museums-Verein, Berlin, Germany

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:67.5 x 50.7 cm

Kaiser-Friedrich-Museums-Verein, Berlin, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$67.45

$67.45

SKU: 2007-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:177 x 129 cm

Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:177 x 129 cm

Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$83.69

$83.69

SKU: 10543-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:92.7 x 68.3 cm

Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Germany

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:92.7 x 68.3 cm

Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$74.95

$74.95

SKU: 9072-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:60 x 48 cm

National Museum, Stockholm, Sweden

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:60 x 48 cm

National Museum, Stockholm, Sweden

Giclée Canvas Print

$61.81

$61.81

SKU: 8944-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:114.3 x 168.6 cm

The Royal Collection, London, UK

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:114.3 x 168.6 cm

The Royal Collection, London, UK

Giclée Canvas Print

$61.81

$61.81

SKU: 7851-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:25.4 x 20.3 cm

The Wallace Collection, London, UK

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:25.4 x 20.3 cm

The Wallace Collection, London, UK

Giclée Canvas Print

$127.97

$127.97

SKU: 10536-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:140.3 x 114.9 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:140.3 x 114.9 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Giclée Canvas Print

$64.12

$64.12

SKU: 9081-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:118.8 x 96.8 cm

Private Collection

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:118.8 x 96.8 cm

Private Collection

Giclée Canvas Print

$89.19

$89.19

SKU: 1997-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:60 x 48 cm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:60 x 48 cm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Giclée Canvas Print

$61.81

$61.81

SKU: 9068-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:47.2 x 38.6 cm

Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, Germany

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:47.2 x 38.6 cm

Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$61.81

$61.81

SKU: 8912-REM

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:28 x 34 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

van Rijn Rembrandt

Original Size:28 x 34 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France