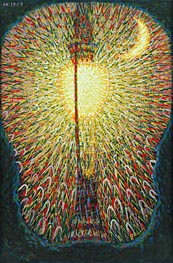

Giacomo Balla Giclée Fine Art Prints

1871-1958

Italian Futurist Painter

1 Giacomo Balla Artworks

SKU: 13365-BGI

Giacomo Balla

Original Size:174.7 x 114.7 cm

Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA

Giacomo Balla

Original Size:174.7 x 114.7 cm

Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA