August Macke Giclée Fine Art Prints 1 of 3

1887-1914

German Expressionist Painter

In the spring of 1914, three painters journeyed to Tunisia. One of them - August Macke - had only months to live. He was twenty-seven years old, newly returned from North Africa, when the war began. By late September, he lay dead on the Western Front. Yet in those final luminous weeks before Europe tore itself apart, Macke produced some of the most radiant paintings of the twentieth century. His life was brief; his contribution to German Expressionism, indelible.

August Robert Ludwig Macke entered the world on 3 January 1887 in Meschede, a small town nestled in the hills of Westphalia. His father, August Friedrich Hermann Macke, worked as a building contractor but harboured artistic ambitions of his own, sketching in his spare hours. His mother, Maria Florentine, came from farming stock in the Sauerland region. Shortly after the boy's birth, the family relocated to Cologne, where young August attended the Kreuzgymnasium between 1897 and 1900. There he formed a lasting friendship with Hans Thuar, himself destined to become a painter. The Thuar household possessed a collection of Japanese woodblock prints - objects that captivated the boy and planted early seeds of aesthetic awareness.

A second move brought the Macke family to Bonn in 1900. Here the thirteen-year-old enrolled at the Realgymnasium and encountered Walter Gerhardt and his sister Elisabeth, who would later become Macke's wife. That same year, a visit to Basel introduced him to the paintings of Arnold Böcklin, whose mythological scenes and moody atmospheres stirred something in the young observer. Between his father's drawings, Thuar's Japanese prints, and Böcklin's symbolist canvases, Macke assembled a private gallery of influences long before he ever held a professional brush.

Tragedy struck in 1904. His father died, leaving the seventeen-year-old to chart his own course. That autumn, Macke enrolled at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, studying under Adolf Maennchen until 1906. Restless and curious, he supplemented his academic training with evening classes under Fritz Helmut Ehmke and took on practical work as a stage and costume designer at the Schauspielhaus Düsseldorf. Travel broadened his eye: northern Italy in 1905, then the Netherlands, Belgium, and Britain the following year. Each journey layered new visual vocabularies onto his developing sensibility.

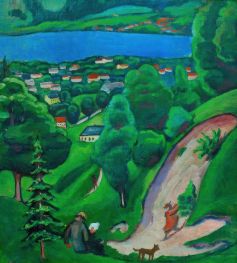

Paris proved decisive. Macke first visited the French capital in 1907 and encountered the Impressionists at firsthand - their broken brushwork, their atmospheric light, their liberation of colour from strict descriptive duty. Returning to Germany, he spent several months in Berlin working in the studio of Lovis Corinth, absorbing lessons in painterly vigour and bold surface handling. His style began to coalesce: French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism formed its foundation, though a Fauvist intensity soon coloured his palette. In 1909, he married Elisabeth Gerhardt, and the couple settled primarily in Bonn, with periodic sojourns to Lake Thun in Switzerland.

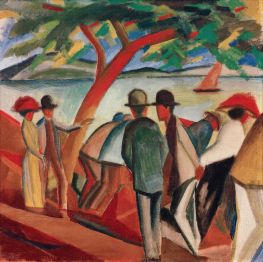

Through his friendship with Franz Marc, Macke entered the orbit of Wassily Kandinsky and the circle forming around Der Blaue Reiter - The Blue Rider - in Munich. For a time, he shared their enthusiasm for spiritual content in art, for the mystical resonance of colour and form freed from representation. Yet Macke remained temperamentally distinct from Kandinsky's increasingly abstract programme. His interests lay in the visible world - in shopfronts and promenades, in women strolling beneath parasols, in the dappled light of parks and cafés. He sought not to abandon appearances but to intensify them.

A turning point arrived in 1912 when Macke met Robert Delaunay in Paris. The French painter's chromatic Cubism - what Guillaume Apollinaire termed Orphism - electrified him. Delaunay's Windows series, with its prismatic fragmentation of light and colour, offered a pictorial language Macke could adapt to his own ends. His painting Shops Windows demonstrates this synthesis: Delaunay's shimmering colour planes merge with the simultaneity of images borrowed from Italian Futurism. The result is neither purely French nor purely German but something personal - a street scene animated by translucent overlapping forms, where figures and reflections dissolve into radiant geometry.

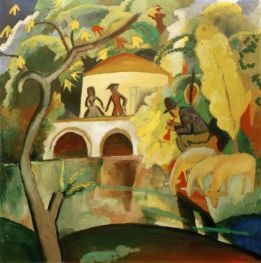

Then came Tunisia. In April 1914, Macke travelled to North Africa alongside Paul Klee and the Swiss painter Louis Moilliet. The seventeen-day trip transformed all three artists, though Macke perhaps most immediately. Confronted with the intense Mediterranean light, the whitewashed architecture, the saturated blues and ochres of the Tunisian landscape, he developed what might be called a luminist approach - colour as light, light as structure. Works from this period shimmer with a crystalline clarity quite distinct from his earlier Fauvist warmth. Türkisches Café, painted shortly after his return, captures the contemplative stillness of figures in an outdoor setting, their forms simplified into interlocking planes of colour. The mood is serene, almost suspended - as though time itself has slowed beneath the North African sun.

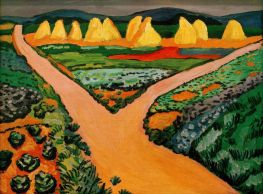

Macke's paintings concentrate on expressing feelings and moods rather than cataloguing objective reality. Colour bends to emotional purpose; form distorts in service of sensation. In this sense, his work belongs firmly within German Expressionism as it flourished between 1905 and 1925, yet his palette and compositional strategies also align him with Fauvism. He occupied a unique position - absorbing successive avant-garde movements arriving from across Europe while maintaining a distinctly personal vision rooted in everyday subjects rendered extraordinary through colour.

War came in August 1914. Macke's final painting, Farewell, registers the darkening atmosphere - figures parting, the weight of impending separation palpable in muted tones and sombre composition. Within weeks, he had enlisted. On 26 September 1914, in the second month of the conflict, August Macke fell at the front in Champagne, France. He was buried in the German Military Cemetery at Souain-Perthes-lès-Hurlus. Twenty-seven years old. Seven years of mature artistic production. A body of work that continues to glow with uncanny vitality.

Perhaps what strikes viewers today is precisely that vitality - the sense that Macke painted as though light itself were a liquid medium to be poured across canvas. His promenades and park scenes radiate an almost painful joy, knowing as we do what followed. Yet there is no foreboding in the work itself, no shadow of coming catastrophe. The paintings remain present-tense, sunlit, alive. August Macke reminds us how much can be achieved in a compressed span, and how swiftly history can extinguish a singular voice.

August Robert Ludwig Macke entered the world on 3 January 1887 in Meschede, a small town nestled in the hills of Westphalia. His father, August Friedrich Hermann Macke, worked as a building contractor but harboured artistic ambitions of his own, sketching in his spare hours. His mother, Maria Florentine, came from farming stock in the Sauerland region. Shortly after the boy's birth, the family relocated to Cologne, where young August attended the Kreuzgymnasium between 1897 and 1900. There he formed a lasting friendship with Hans Thuar, himself destined to become a painter. The Thuar household possessed a collection of Japanese woodblock prints - objects that captivated the boy and planted early seeds of aesthetic awareness.

A second move brought the Macke family to Bonn in 1900. Here the thirteen-year-old enrolled at the Realgymnasium and encountered Walter Gerhardt and his sister Elisabeth, who would later become Macke's wife. That same year, a visit to Basel introduced him to the paintings of Arnold Böcklin, whose mythological scenes and moody atmospheres stirred something in the young observer. Between his father's drawings, Thuar's Japanese prints, and Böcklin's symbolist canvases, Macke assembled a private gallery of influences long before he ever held a professional brush.

Tragedy struck in 1904. His father died, leaving the seventeen-year-old to chart his own course. That autumn, Macke enrolled at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, studying under Adolf Maennchen until 1906. Restless and curious, he supplemented his academic training with evening classes under Fritz Helmut Ehmke and took on practical work as a stage and costume designer at the Schauspielhaus Düsseldorf. Travel broadened his eye: northern Italy in 1905, then the Netherlands, Belgium, and Britain the following year. Each journey layered new visual vocabularies onto his developing sensibility.

Paris proved decisive. Macke first visited the French capital in 1907 and encountered the Impressionists at firsthand - their broken brushwork, their atmospheric light, their liberation of colour from strict descriptive duty. Returning to Germany, he spent several months in Berlin working in the studio of Lovis Corinth, absorbing lessons in painterly vigour and bold surface handling. His style began to coalesce: French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism formed its foundation, though a Fauvist intensity soon coloured his palette. In 1909, he married Elisabeth Gerhardt, and the couple settled primarily in Bonn, with periodic sojourns to Lake Thun in Switzerland.

Through his friendship with Franz Marc, Macke entered the orbit of Wassily Kandinsky and the circle forming around Der Blaue Reiter - The Blue Rider - in Munich. For a time, he shared their enthusiasm for spiritual content in art, for the mystical resonance of colour and form freed from representation. Yet Macke remained temperamentally distinct from Kandinsky's increasingly abstract programme. His interests lay in the visible world - in shopfronts and promenades, in women strolling beneath parasols, in the dappled light of parks and cafés. He sought not to abandon appearances but to intensify them.

A turning point arrived in 1912 when Macke met Robert Delaunay in Paris. The French painter's chromatic Cubism - what Guillaume Apollinaire termed Orphism - electrified him. Delaunay's Windows series, with its prismatic fragmentation of light and colour, offered a pictorial language Macke could adapt to his own ends. His painting Shops Windows demonstrates this synthesis: Delaunay's shimmering colour planes merge with the simultaneity of images borrowed from Italian Futurism. The result is neither purely French nor purely German but something personal - a street scene animated by translucent overlapping forms, where figures and reflections dissolve into radiant geometry.

Then came Tunisia. In April 1914, Macke travelled to North Africa alongside Paul Klee and the Swiss painter Louis Moilliet. The seventeen-day trip transformed all three artists, though Macke perhaps most immediately. Confronted with the intense Mediterranean light, the whitewashed architecture, the saturated blues and ochres of the Tunisian landscape, he developed what might be called a luminist approach - colour as light, light as structure. Works from this period shimmer with a crystalline clarity quite distinct from his earlier Fauvist warmth. Türkisches Café, painted shortly after his return, captures the contemplative stillness of figures in an outdoor setting, their forms simplified into interlocking planes of colour. The mood is serene, almost suspended - as though time itself has slowed beneath the North African sun.

Macke's paintings concentrate on expressing feelings and moods rather than cataloguing objective reality. Colour bends to emotional purpose; form distorts in service of sensation. In this sense, his work belongs firmly within German Expressionism as it flourished between 1905 and 1925, yet his palette and compositional strategies also align him with Fauvism. He occupied a unique position - absorbing successive avant-garde movements arriving from across Europe while maintaining a distinctly personal vision rooted in everyday subjects rendered extraordinary through colour.

War came in August 1914. Macke's final painting, Farewell, registers the darkening atmosphere - figures parting, the weight of impending separation palpable in muted tones and sombre composition. Within weeks, he had enlisted. On 26 September 1914, in the second month of the conflict, August Macke fell at the front in Champagne, France. He was buried in the German Military Cemetery at Souain-Perthes-lès-Hurlus. Twenty-seven years old. Seven years of mature artistic production. A body of work that continues to glow with uncanny vitality.

Perhaps what strikes viewers today is precisely that vitality - the sense that Macke painted as though light itself were a liquid medium to be poured across canvas. His promenades and park scenes radiate an almost painful joy, knowing as we do what followed. Yet there is no foreboding in the work itself, no shadow of coming catastrophe. The paintings remain present-tense, sunlit, alive. August Macke reminds us how much can be achieved in a compressed span, and how swiftly history can extinguish a singular voice.

64 August Macke Artworks

Page 1 of 3

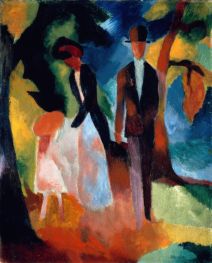

Giclée Canvas Print

$65.28

$65.28

SKU: 19956-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:35.5 x 25 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

August Macke

Original Size:35.5 x 25 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

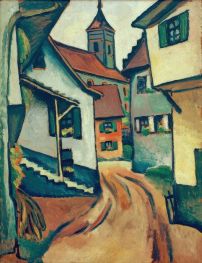

Giclée Canvas Print

$80.04

$80.04

SKU: 19947-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:81 x 100.5 cm

Von der Heydt Museum, Wuppertal, Germany

August Macke

Original Size:81 x 100.5 cm

Von der Heydt Museum, Wuppertal, Germany

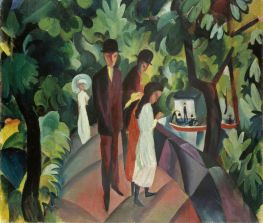

Giclée Canvas Print

$65.28

$65.28

SKU: 19945-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:129.5 x 230.5 cm

Museum fur Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Dortmund, Germany

August Macke

Original Size:129.5 x 230.5 cm

Museum fur Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Dortmund, Germany

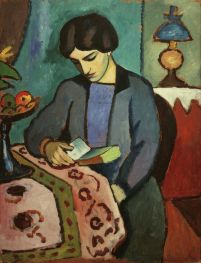

Giclée Canvas Print

$80.95

$80.95

SKU: 19954-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:61 x 48 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

August Macke

Original Size:61 x 48 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$75.37

$75.37

SKU: 19943-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:81 x 105 cm

Kunstmuseum, Bern, Switzerland

August Macke

Original Size:81 x 105 cm

Kunstmuseum, Bern, Switzerland

Giclée Canvas Print

$65.28

$65.28

SKU: 19960-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:30 x 35 cm

Private Collection

August Macke

Original Size:30 x 35 cm

Private Collection

Giclée Canvas Print

$65.28

$65.28

SKU: 19951-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:41 x 32.5 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

August Macke

Original Size:41 x 32.5 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$98.93

$98.93

SKU: 19941-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:89 x 89 cm

Private Collection

August Macke

Original Size:89 x 89 cm

Private Collection

Giclée Canvas Print

$73.21

$73.21

SKU: 19965-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:80.5 x 60 cm

Private Collection

August Macke

Original Size:80.5 x 60 cm

Private Collection

Giclée Canvas Print

$98.57

$98.57

SKU: 19963-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:71.4 x 71.2 cm

Private Collection

August Macke

Original Size:71.4 x 71.2 cm

Private Collection

Giclée Canvas Print

$80.95

$80.95

SKU: 19953-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:62.5 x 75.3 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

August Macke

Original Size:62.5 x 75.3 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$80.95

$80.95

SKU: 19962-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:55 x 45 cm

Kunstmuseum, Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany

August Macke

Original Size:55 x 45 cm

Kunstmuseum, Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$71.94

$71.94

SKU: 19952-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:60 x 82 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

August Macke

Original Size:60 x 82 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$73.21

$73.21

SKU: 19958-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:47.5 x 64 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

August Macke

Original Size:47.5 x 64 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$85.80

$85.80

SKU: 19955-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:48 x 56 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

August Macke

Original Size:48 x 56 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$89.39

$89.39

SKU: 19964-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:60.5 x 55 cm

Museum Ostwall, Dortmund, Germany

August Macke

Original Size:60.5 x 55 cm

Museum Ostwall, Dortmund, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$79.86

$79.86

SKU: 19944-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:60 x 48.5 cm

Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe, Germany

August Macke

Original Size:60 x 48.5 cm

Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$86.34

$86.34

SKU: 19950-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:66 x 57.5 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

August Macke

Original Size:66 x 57.5 cm

Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$76.09

$76.09

SKU: 19961-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:103 x 80 cm

Museum für Neue Kunst, Freiburg, Germany

August Macke

Original Size:103 x 80 cm

Museum für Neue Kunst, Freiburg, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$83.40

$83.40

SKU: 19949-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:51 x 50 cm

Private Collection

August Macke

Original Size:51 x 50 cm

Private Collection

Giclée Canvas Print

$84.00

$84.00

SKU: 19942-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:86 x 100 cm

Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt, Germany

August Macke

Original Size:86 x 100 cm

Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$65.28

$65.28

SKU: 19959-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:46 x 36 cm

Private Collection

August Macke

Original Size:46 x 36 cm

Private Collection

Giclée Canvas Print

$75.73

$75.73

SKU: 19946-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:105 x 81 cm

Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany

August Macke

Original Size:105 x 81 cm

Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany

Giclée Canvas Print

$65.28

$65.28

SKU: 19948-AMK

August Macke

Original Size:49.7 x 34 cm

LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur, Munster, Germany

August Macke

Original Size:49.7 x 34 cm

LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur, Munster, Germany